Cowpea is an important grain legume crop widely grown for human food, livestock fodder, and feeds. It is widely recognized as a staple dietary protein source, rich in micronutrients such as iron and zinc, especially in Africa and Asia, where they are predominantly consumed. The amino acid profiles of grain legumes are complementary to those of cereals, such that consuming them together improves the nutritional effectiveness of cereal-dominated diets of low-income earners. Cowpea food is also low in glycemic index; consuming it reduces the risk of obesity and diabetes. One major way of utilizing this legume crop is through food processing, “converting the raw materials into semi-finished and finished products that can be consumed or stored”. The food can be processed at different levels, including home-based food processing and at the industrial level (Plate 1). Industrial food processing could be at the cottage level or on a large scale.

There has been a growing interest in interventions in agriculture to become more nutrition-sensitive. Nutrition is a critical part of health, and poor health reduces work performance, income, and productivity in agricultural communities. Various entry points have been identified to design nutrition-sensitive agriculture (Jaenicke and Virchow, 2013). One of the strong openings is to boost the production of nutritious foods and maintain food quality. This can be achieved by expanding the production of nutrient-dense crops such as cowpea and reducing grain contamination from pesticide residue by limiting the use of hazardous chemicals for grain storage.

Women’s participation in legume seed systems is rapidly changing in northern Nigeria in response to various factors, including enhanced access to technologies, increased urbanization, the shift in diets, improvements in farmers’ education and health, institutional and policy reforms, and investments in rural infrastructure. Consequently, gender integration of the smallholder legume seed system is changing food markets and helping to create new income opportunities and a more dynamic environment in which new technologies and agricultural practices can contribute to helping smallholder farmers respond to climate change, which are critical challenges facing the food industry. Climate-sensitive health risks disproportionately impact women. Therefore, solutions should address gender disparities in access to food, health care, education, and economic well-being. Engaging more women in legume seed systems will ensure gender equality and inclusion.

Agriculture, climate change, health and wealth

Climate change can disrupt food availability, reduce access to food, and affect food quality. The adverse effect of climate change will put people’s food supplies at risk, particularly in developing nations, which can drive down crop yields, destroy livestock, and interfere with food transport. This will eventually affect human health and development progress and jeopardize future generations’ health, well-being, and livelihoods, with a remarkable impact on women.

What does food have to do with climate change?

Let me say here that what we eat and how that food is produced affects our health and the environment. Food must be grown, processed, transported, distributed, prepared, consumed, and sometimes disposed of. Each step creates greenhouse gases that trap the sun’s heat and contribute to climate change. Studies have shown that about a third of all human-caused greenhouse gas emissions are linked to food.

What are the foods that cause the most greenhouse gas emissions?

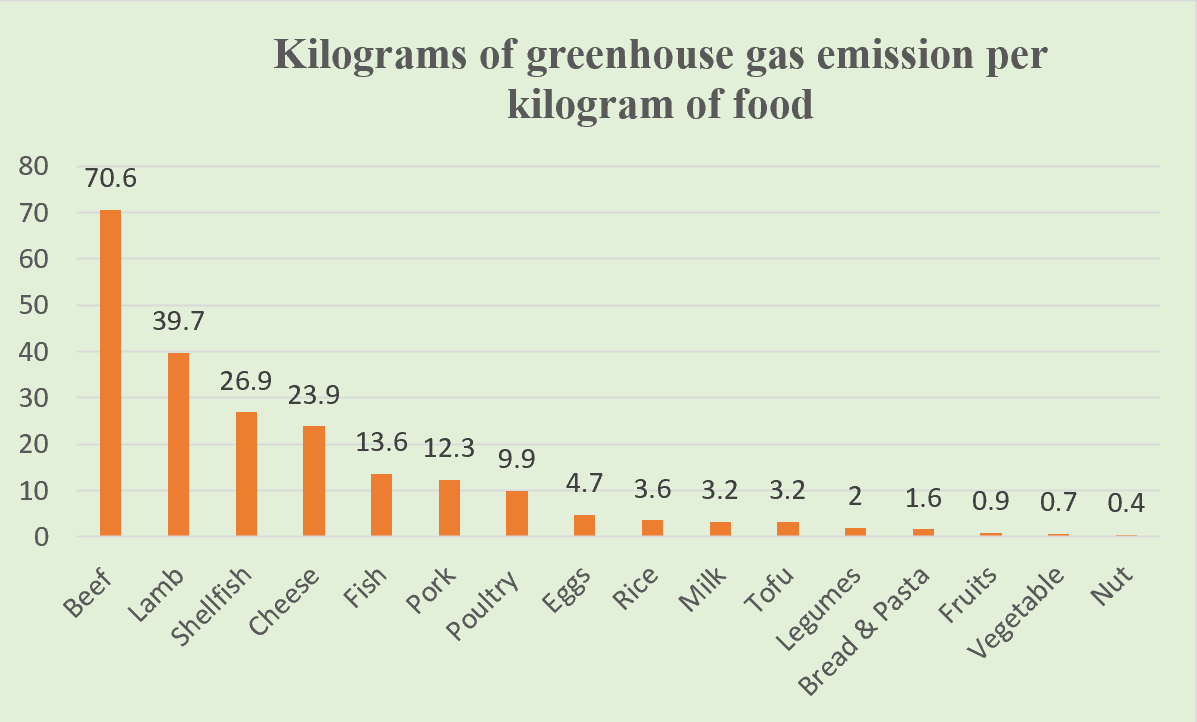

The climate impact of food is measured in terms of the intensity of greenhouse gas emissions. The emissions intensity is expressed in kilograms of “carbon dioxide equivalents”—which includes not only CO2 but all greenhouse gases—per kilogram of food, per gram of protein or calorie. Animal-based foods, especially red meat, dairy, and farmed shrimp, are generally associated with higher greenhouse gas emissions than plant-based foods.

However, plant-based foods such as whole grains (cowpeas and beans) are among the few that have lower greenhouse gas intensities than animal-based foods. Legumes generally use less energy, land, and water. Figure 1 shows the carbon footprint of other food products. Emissions can be compared based on weight (per kilogram of food) or in terms of nutritional units (per 100 grams of protein or 1000 kilocalories)

The chart shows that emissions can be compared based on weight (per kilogram of food) or in terms of nutritional units (per 100 grams of protein or 1000 kilocalories), which shows us how efficiently different foods supply protein or energy (Poor and Nemeck, 2018).

This suggests that greenhouse gas emissions from the food sector can be reduced if we shift food systems toward plant-rich diets with more plant protein (such as cowpea), a reduced amount of animal-based foods (meat and dairy), and less saturated fats (butter, milk, cheese, meat, coconut oil, and palm oil) will reduce greenhouse gas emission and improve health. Cowpea is, therefore, a strategic crop for climate change adaptation and good nutrition.

Globally, women play a vital role in the food industry, particularly in leadership and innovation. Empowering women and facilitating sustainable access to high-value markets will enable smallholder farmers to increase their incomes, effectively reducing poverty and improving livelihoods. Many women have participated in the legume value chains as producers, traders, processors, retailers, and consumers. Women’s inclusion in improving the performance of legume value chains can thus benefit many people—a way of adapting to climate change and improving human health. A testament to this fact is the technical collaboration with diverse partners that led to the creation of a new value chain (processing and utilization of cowpea and soybean food to reduce malnutrition).

In 2023, IITA collaborated with the Kano State Agro-pastoral Development Project (KSADP) to train women in legume production, food processing for household nutrition, and income generation (Plate 2). IITA also collaborated with HarvestPlus to strengthen the legume food chain and support female-led food businesses to enable female workers and leaders to overcome the constraints they face in achieving full economic participation. The partnership works along the food systems to meet the needs of all people regardless of their socioeconomic status. Empowering women is believed to provide more opportunities to drive social change and maximize their potential contributions to the economy and society.

There are clear signs that food industries significantly impact economic development and poverty reduction in urban and rural communities. Changes in and around the agri-food sector can contribute to developing better support services for farmers, such as technology and financial products, and advancing health and nutrition. Evidence has shown that small producers with access to technical support services are more willing to adopt new technologies and invest in exploiting emerging market opportunities. Seed Equal has developed various interventions in legume seed systems and associated markets. These have focused on research for development programs that emphasize increasing food production and productivity, as well as the commercialization and development of inclusive value chains. This approach was initially developed to increase the competitiveness and improve the livelihoods of smallholder legume producers, which has proved helpful in northern Nigeria and other parts of West Africa. The food industry has made progressive changes in recent years, promoting gender equity (Plate 3).

Smallholder farm households consume and sell grain legume crop products as human food, livestock fodder, and feed, which are in demand locally and in urban and export markets. Over 75% of farming households consumed cowpeas they produced and sold the surplus to local traders. Production is mainly for the domestic market; however, small volumes of exports are carried out. A few large-scale trading companies dominate the supply of cowpeas on the national market. These traders and off-takers purchase cowpea from smallholder farmers and store, process, and sell the grain in bulk.

However, over the last decade, the low quality of produce at the grain market has discouraged traders and processors from purchasing grains from farmers, especially for the export market, due to chemical contamination during storage. Several cases of food poisoning have been reported after consuming meals made from cowpeas. The reason is that grains produced are stored using hazardous chemicals, raising concerns about food quality and safety. However, proper post-harvest handling of cowpeas will prevent both quantitative (a reduction in weight and volume) and qualitative (food and reproductive value) losses and improve food quality and safety.

It is on this premise that IITA—under the One CGIAR initiatives on Seed Equal, work page 2, ‘Boosting Legume Seed through a demand-led Approach’—is making giant efforts aimed at building the technical capacity of large-volume grain traders and aggregators to improve cowpea storage and handling practices to supply high-quality grain to meet the demand of the grain market and that of other buyers. This will also strengthen the collaboration and linkages between smallholder grain producers, traders, and aggregators to ensure that high-quality grain is produced and supplied to meet the needs of the different customers and that the beneficiaries receive nutritious and safe food (Plate 4).

Plate 4: Training grain traders and off-takers on proper post-harvest handling and storage of cowpea.

This partnership between smallholder farmers and traders/aggregators will further open market opportunities and inform farmers of the kind and volumes of grain demand in the market. This behavioral change will facilitate and boost cowpea production and commercialization, pushing for improved legume seed demand, primarily as the grain market is segmented by variety and consumer preferences. This will expand grain production and farmers’ use of improved seeds and help them improve their incomes from sales to high-quality markets. Improved cowpea technology adoption will increase production and productivity but will only lead to better income and health benefits with the integration of women. Most farmers need more access to market information or trusted buyers to sell their surplus production. With the engagement of off-takers and aggregators in the cowpea value chain, these traders will purchase cowpea from smallholder farmers’ stores, and process and sell the cowpea during the year. Thus providing the smallholder grain farmers with a guaranteed market. These traders-grain farmers’ linkages will pull the seed market.

The low prices offered to farmers due to the poor quality of the grain resulting from poor post-harvest handling discourage farmers from investing in cowpea production. Thus, most farmers use their own-saved seeds with little fertilizer and pesticide application. However, if smallholder farmers are empowered to improve the quality of their grains, off-takers could offer better prices; this will help improve their incomes from sales and encourage the use of quality seeds of improved varieties and participation in the grain market if the perceived benefit by farmers turns out positive. Also, cowpea farmers would go for better varieties that produce higher yields. The perceived benefits to cowpea farmers from adopting improved seeds include market-preferred traits, higher profitability, better incomes, and food security.

Most farmers have limited access to market information or trusted buyers for their surplus cowpea production. The off-taker/aggregation model can benefit cowpea farmers by making a more significant impact on better prices, customer behavior, market dynamics, risk reduction, better decisions on which grain to invest in, and positive networking. Quick access to an assured market helps farmers make better decisions and improve product services and communications. Aggregated farm produce can help to comply with regulatory requirements and standards. This will also help guide public and private investment in the supply and demand of grain quality traits. For example, the market pulls (by consumers and producers) for brown or white varieties are strong, but traders face inadequate supply to meet the demand. Value chain actors should support smallholder farmers based on market demand to benefit from specific grain quality traits, quantity, and promising grain market. Grain off-takers and aggregators provide consumer-based decisions to farmers and researchers. They bridge the gap between researchers and farmers in technology development and promotion. Improved aggregator-farmer linkages will assist farmers and marketers in understanding customer needs, behaviors, purchase patterns, and grain choices.

A visit to the aggregator’s warehouse in the DAWANAU market reveals that many have warehouses with the capacity to store over 1000 metric tons of grain (Plate 5). However, most aggregators cannot meet their grain demand due to inadequate grain supply. Only 45% of their grain demand is sourced from the Nigerian market; hence, they depend on importation from neighboring countries like Niger and Chad. The shortfall may be due to low production or non-availability of the customers’ preferred grain types. We also learned from the aggregators that grain size and eye (helium) color preferences vary from place to place, implying that the cowpea grain market is segmented. For example, in some markets in the southwest, consumers generally prefer large grains, so prices of smaller grains and those damaged by insect pests are discounted.

The most common preference for testa color is brown or speckle, but consumers prefer white grains in some areas. When asked about the market in Lagos, the aggregators remarked that cowpea grain size was not a big issue because Lagos is a cosmopolitan city, all types of cowpea dishes are prepared, and demand exists for the different grain sizes and colors. Still, large seeds with brown color receive a premium price. These suggest that seed systems and production research should promote varied portfolios that respond to regional differences in consumer preferences for grain characteristics to meet the market’s needs. Within the framework of this arrangement in the last two years, we facilitated linkages between off-takers and grain farmers’ which led to sales of over 58,333 tons of quality grain of three improved varieties (SAMPEA 11, FUAMPEA 3 and FUAMPEA 4) high in protein, zinc and iron worth US $46,666 in the grain market. This off-taker-farmers arrangement has helped to pull over 972 tons of certified seed of the improved varieties.

Plate 5. Mallam Isa, an aggregator at DAWANU Market in Kano, Nigeria, with cowpea grains ready for shipment to southern Nigeria for sale.

Conclusion

The strategy of enhancing grain quality for cowpea trade through fostering collaborations and addressing market challenges is insightful and transformative. The report highlights the effectiveness of Multi-Stakeholder Platforms (MSPs) in creating sustained demand and supply of quality cowpea and promoting improved legume varieties. The robust aggregator-farmer linkage model and collaboration among the different value chain actors are crucial for enhancing the quality of the grain market, food security, job creation, income generation, and improving the actors’ livelihoods.

Contributed by Lucky O. Omoigui, Alpha Y. Kamara, Abdulwahab S. Shaibu, Yusuf D. Fouad, S. Boahen, Reuben Solomon and Paul Aseete.

References:

Jaenicke H. and D. Virchow, 2013. Entry points into a nutrition-sensitive agriculture Food Security, 5 (2013), pp. 679-692, 10.1007/s12571-013-0293-5

Royer A, Bijman J, Bitzer V (2016) Linking smallholder farmers to high-quality food chains: appraising institutional arrangements. In: Bijman J, Bitzer V (eds) Quality and innovation in food chains. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, pp 33–62. Chapter 2

No Comments